Censorship

February 8, 2015

Freedom of artistic expression has been the subject of intense discussion (and unfortunately not only discussion) lately, from Sderot to Paris. Two experiences in which I agreed to, or even initiated, a kind of censorship of my work, may shed a slightly different light on the subject.

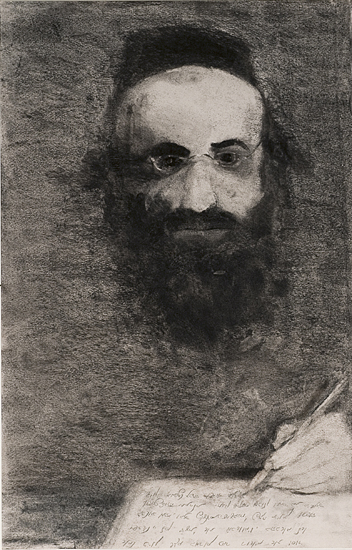

The more recent story began about two months ago with a request from an editor of a magazine aimed at the ultra-Orthodox public, to use this image:

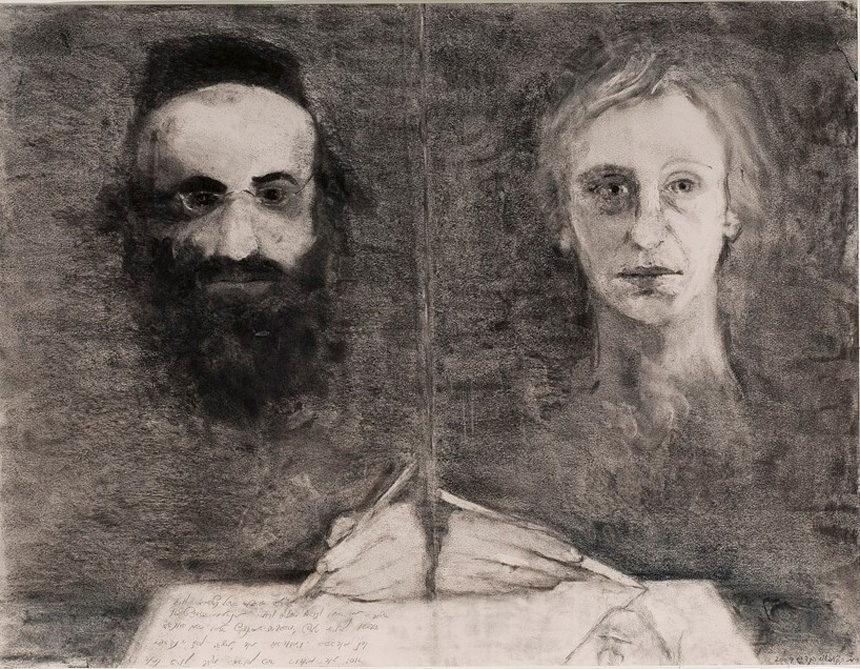

I explained that this is a partial image, and that the whole drawing looks like this:

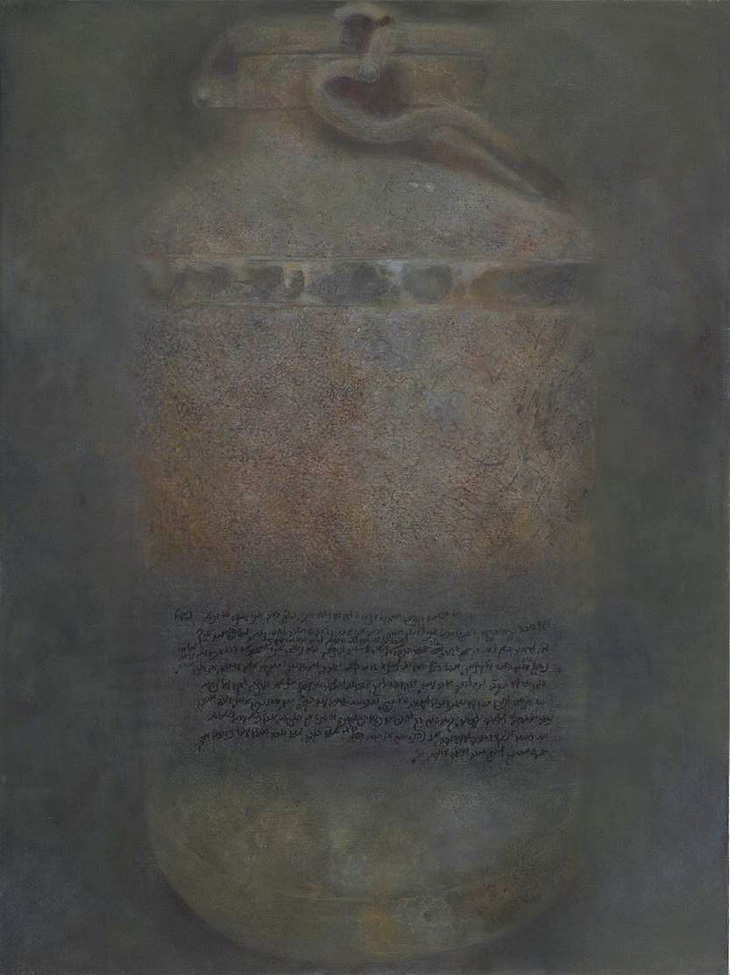

and that it portrays an imagined encounter between Rabbi Kalanymos Shapira, the Piaseczna Rebbe (next to whose writings the image was to appear) and the painter Malva Schalek, part of my series of paintings The Painter and the Hassid which featured these two figures, who perished in the Holocaust but whose work survived, hidden. The editor explained that he cannot publicize an image showing a woman next to the Rabbi, but to his credit added that he wouldn’t dream of requesting that I approve cropping the image. For some reason, in addition to suggesting other images from the series that do not include people at all (such as the one on the left showing the milk jug in which the Rabbi’s writings were hidden) I also mentioned that it is customary practice to show parts of artworks, as long as the caption states that it’s a detail. We agreed that I would consider that option. I subsequently agreed to showing the partial image, on condition that a text written by me would accompany it. My thinking was that through the text I would provide a place for the erased female image, and thus invite interested readers to seek out the whole image. I viewed this as a opportunity for dialogue with a different and distant community.

When I understood that the magazine’s policy forbids portrayal of women altogether (and not just in the unusual fantastic-historical setting that I had created), I was distressed. Continuing my correspondence with the editor, I was pleased to discover that he is a staunch opponent of this policy, and has written against it in various forums where he even defined it as opposed to Jewish law. The fact that he remains anonymous here and in those forums is testimony to how tense this controversy is. After this exchange I felt, again, how fortunate I was to take part in a meaningful conversation that crossed over chasms of segregation.

However, together with my pleasure at this rare conversation came the realization that in the end result I cooperated with the erasure of women, since in addition to the cropping of the image, the text that I added was also edited in such a way that only an extremely discerning reader could recognize and seek out the presence of the missing female figure.

The second story took place years ago, when I was working on a painting based on the illuminated Moslem manuscript the Miraj-Nameh, which describes the night journey of Mohammed to the “distant mosque” which their tradition places on Jerusalem’s Temple Mount.

Two pages from the Miraj-Nameh manuscript, originating in15th Century Herat (today western Afghanistan), National Library of France, Paris. Mohammed meets Moses (at left) and various prophets (at right).

At the time I was in contact with Hasna, a Moslem woman working in the building where I rented a studio, and whom I had painted previously. When I showed her the book with the illuminations showing Mohammed and the prophets, she was shocked that someone would portray them in painting, and even more so when she learned that the illuminator was a fellow Moslem. It’s interesting to note that she was no less disturbed by the portrayals of Abraham, Moses, and other biblical figures, alongside Jesus, as she was by the portrayal of Mohammed. I recall her describing a physical reaction to seeing the Miraj-Nameh, a shivering in her arms.

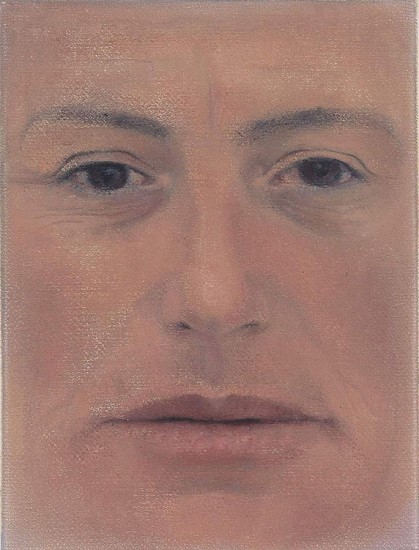

When I proceeded to create my own variation on the nocturnal encounter between Mohammed and Moses, Hasna’s true expression of offense was one of the factors in my decision to refrain from portraying their facial features. In this case my partial consideration of her (and other viewers’) feelings worked in the painting’s favor, as the original Mongolian features of the figures in the manuscript did not interest me, while on the other hand I am fascinated by the religious tension around portraying faces, which appears in some Jewish sources as well (and which I touched on in previous works, such as here and here). I call this partial consideration since according to many Moslems even this faceless, general portrayal is a terrible transgression. Should I go underground?

A few words on the painting: At center, the meeting between Mohammed and Moses. At left, two modern prophets, my childhood heroes – Martin Luther King and Mahatma Ghandi. At right, my mother and grandmother, the former smiling and the latter looking worried. Can the meeting take place?

I shared these two stories in order to reflect on the complicated encounter between art and traditional populations (even without the intervention of people from the worlds of art, religion, and politics, some of them with a vested interest in maximizing the confrontation), while examining the issue of freedom of expression – suggesting that it may include the placing of limitations by the artist herself, voluntarily, and not as part of a struggle with outside forces, or due to exaggerated fear or conservatism (though I happen to be pretty scared and conservative myself, but that’s beside the point). And also to ask how and where to include, in the glossary of terms associated with contemporary art, alongside freedom, the rejection of conventions, and many more worthy concepts relevant to an open society, the word responsibility.

A few endnotes:

- Regarding the missing woman from the magazine – there may be hope for at least partial repair. Due to many errors in the edition that included my work, in the next one there will be a place for corrections. This time I will insist that at least the text will appear in full.

- From the Lost and Found Department: the drawing The Painter and the Hassid that appears above traveled in 2011 to an exhibit in Dusseldorf and never returned. If anyone has seen it, please contact me.

- It was fun to discover that this essay, on the Charlie Hebdo saga, opens with a page from a similar illuminated manuscript of the Miraj. And, for Hebrew readers, this conversation on the controversy surrounding one of the controversial works at the exhibit at the Sapir College in Sderot, is refreshing as it doesn’t just duplicate pre-written and expected arguments, as often happens in these cases. This post was an attempt to make another contribution in that direction.

2 Responses to “Censorship”

[…] Censorship Read […]

I am dealing with this very issue with the solo show at art gallery iMiklat Omanut, in the Haredi neighborhood. of Makor Baruch in Jerusalem. It makes me very crazy, but I a made some peace with it and the show looks very good.

It would be great to have an exhibit where I could show what I want.

I talked about this very topic of censorship on the radio in an interview with Ilene Prusher on the weekend edition of TLV1.FM. To hear it, go to

I hope you will come to see the show, Ruth, and this topic will probably come up at the gallery talk on Feb 19th.

Comments are closed.