Prayer Rugs Gallery Page

Prayer Rugs

Yifat Ben-Natan, The New Artists’ Colony Gallery, Tivon, 2004

In the exhibition “Prayer Rugs” Ruth Kestenbaum Ben-Dov shows two series of paintings that stem from a common source, and she raises difficult and deep questions about the existential reality in our region. Rather than providing answers, Ben-Dov carries the questions to their extreme, examining how close she can come to reaching the essence of the problem. Ben-Dov’s statement does not express a clear political stance, but rather reflects on the emotional and spiritual connection between the land and its residents, and she attempts to understand this bond as it is manifested in the reality of life. The paintings express collective questions about the ability (or impossibility) of two peoples to live peacefully in the conflict-ridden land of Israel, while penetrating the mystical dimension of those peoples’ connection with the land, and raising personal questions about faith and prayer.

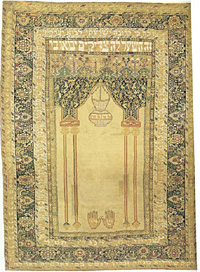

The series “Prayer Rugs” grew through observation of an ancient parochet (Torah curtain) from the collection of the Jewish Museum in New York.The paintings are variations on the imagery of the curtain, which looks like a hanging carpet, and contains elements borrowed from Muslim prayer rugs. At the bottom of the original piece is the dedication by a father in memory of his late daughter, an element that became more and more charged as the series progressed. In this object Ruth Ben-Dov found a visual representation of an encounter between Judaism and Islam, and this enabled her to touch visually on such disturbing issues as the existence of two religions with claims to truth and to exclusive ownership of the land. As a resident of the Galilee, where these questions form a part of daily life, she confronts the central theme of the meaning of the land.

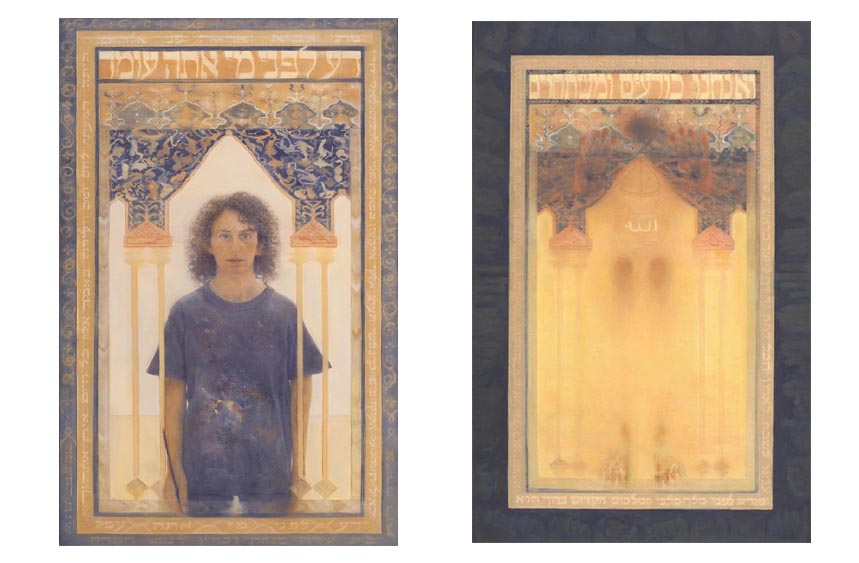

Throughout the series, contrasting themes relating to the ritual practices of the two religions appear. These motifs are intertwined, and Ben-Dov purposely makes it difficult to identify where one begins and the other ends. The texts, taken from Jewish prayers and other religious sources, in many cases in Arabic translation, strengthen the impression of a complex and intricate interconnection, and the experience of a bond that is beyond the physical. Examination of the contrasts is first expressed in the bodily state of the person in prayer – prostrated on a carpet versus standing opposite a curtain. This leads to the basic juxtaposition between the earth as a physical essence and an act of prayer that stems from a wish to transcend physical reality, opposing tendencies that nonetheless possess the possibility of complementarity.

By portraying her own image standing opposite or inside the curtain, parallel or in contrast to bodily poses of prostration while praying or kissing the ground, Ben-Dov hints that the connection to the land is transcendent, that the earth itself has added qualities. Through feelings of closeness and love, the bond with the earth grows more and more essential, until it is finally portrayed by the image of the grave, in which the human body fuses completely with the ground. On the other hand, this may be viewed as a statement of protest at the many victims that the land claims.

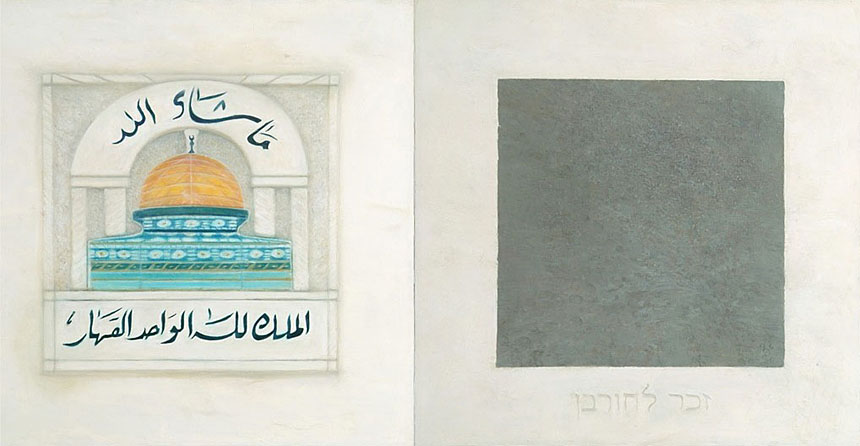

The second series of paintings, “Zecher-Remembrance” (a series in formation) is based on two central images (or an image and “non-image”) that point to the same place. The first image is a grey square, both abstract and real. The square represents the unpainted patch of a wall that can be found in some traditional Jewish homes in memory of the destruction of the Temple. This image-non-image, void of content and color, symbolizes emptiness, or a space waiting to be filled. The grey square may be seen as an expression of a collective expectation of rebuilding out of destruction. Next to the grey square, Ben-Dov juxtaposes a painting of the same dimensions, portraying a tile depicting the Dome of the Rock, something that adorns the

exterior of many Muslim homes.

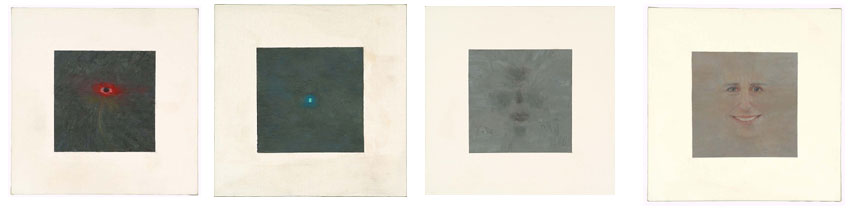

In a third painting, the grey square expands to cover most of canvas area. In its center, Ben-Dov painted a copy of an early print showing the Temple in the image of the Dome of the Rock, as it was imagined by Jews in the Diaspora.

In this series, inspired by visits to two homes in the Galilee bearing these images on their walls, the artist reiterates questions of identity and attachments. Is there a necessary connection between my destruction and the other’s growth, and vice versa? Does one people’s identity necessarily need to be based on the negation of the other’s? Ruth Kestenbaum Ben-Dov discovers additional meaning in the grey square, leading her to create new images growing out of it. In going beyond these existential and concrete themes, she points to the square as a missing piece, as a basic aspect of being, an understanding that life is essentially loss and that its driving force is a wish to be filled.