In the Body of the Text

Word and Image

This series from 1998-1999 explores the connection and tension between text and painting, between word and image, by juxtaposing or combining the two within the works themselves. Many of the texts are ancient Jewish sources relating to the permitted and prohibited forms of representation. More on this series in the catalog which accompanied the 1999 exhibition at the Janco-Dada Museum.

You are invited to see the images without explanations – without more words than those included in them – in the following slideshow, and then scroll down to learn more about each work.

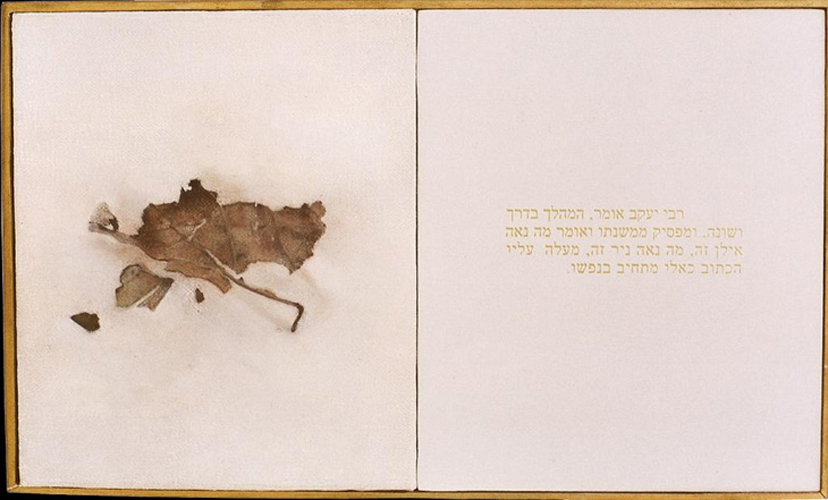

Reading Trees

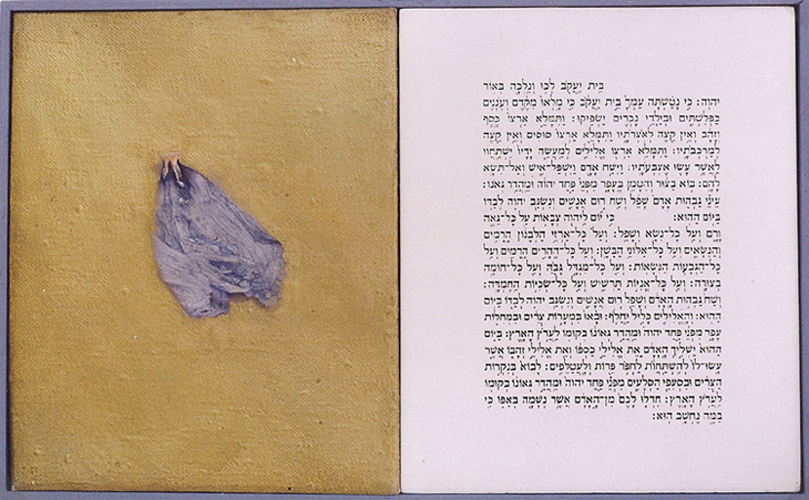

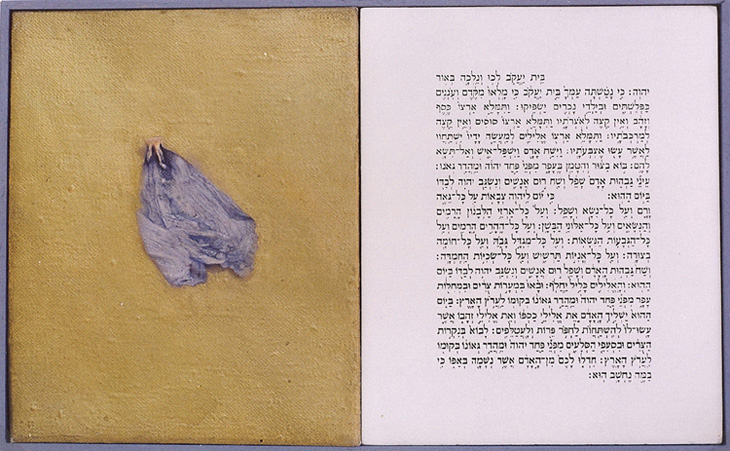

Turn away from Man, 1998, oil on canvas and text screen-printed on wood (Isaiah 2, 5-25), 19 X 30 cm, private collection, New York

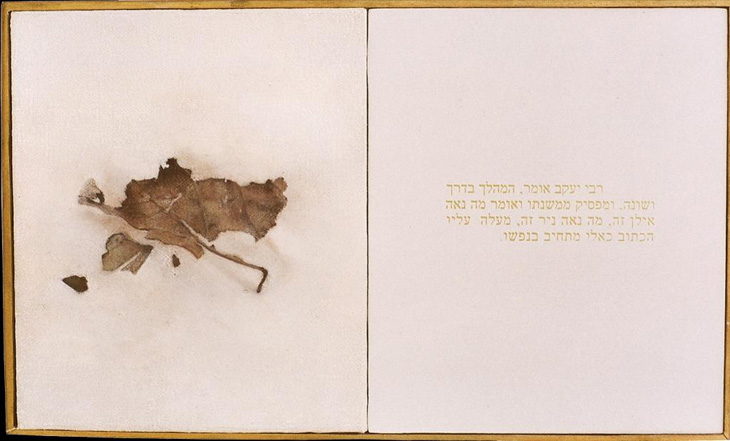

Reading Trees, 1998, oil on canvas and text screen-printed on wood (Ethics of the Fathers 3, 9), 19 X 30 cm, private collection, New York

In the two paintings above, I began experimenting with pairing printed text on a panel with a painting on canvas, exploring whether the two languages can join to create one visual work while remaining in tension with one another. In Turn away from Man the text from Isaiah criticizes gold, and the “eyes of man” are related to pride, idolatry, and obsession with material and physical greatness. Next to the text is a painting of a delicate and small leaf, thougth on a background of the accursed gold. In Reading Trees the text presents a very extreme view of the denial of visual pleasure: “Rabbi Jacob says: ‘He who travels on the road while reviewing what he has learned, and interrupts his study and says: ‘How fine is that tree, how fair is that field!’ Scripture regards him as if he committed a mortal sin”. The image of the dying leaf echoes the death sentence rendered by the text, but suggests that art is concerned not only with external beauty or prettiness. Here the text is rendered in gold, in sharp contrast to the dark colors of the leaf, yet somewhat ironically adorning its anti-visual message.

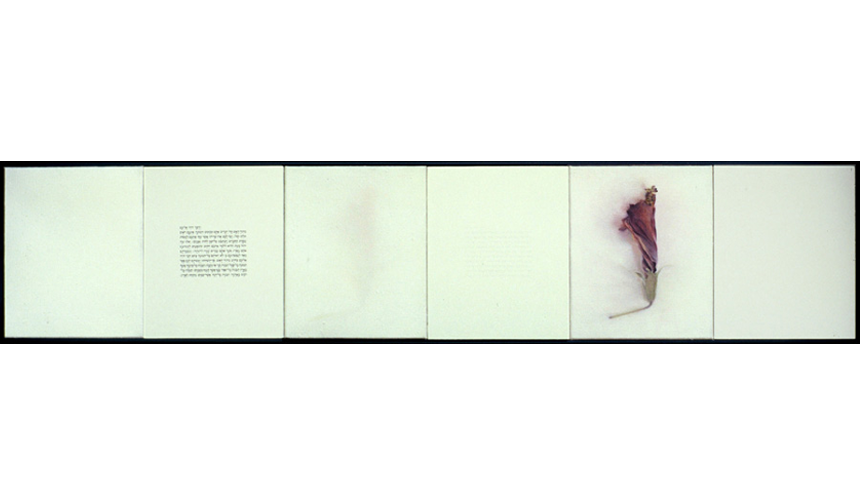

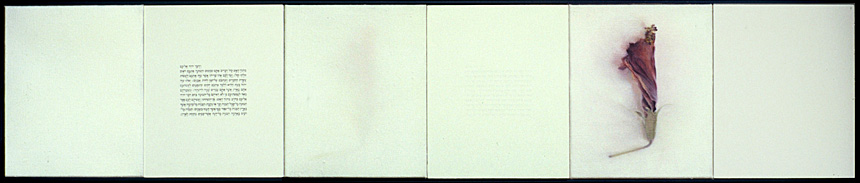

Only a Voice, 1998, oil on canvas and text screen-printed on wood (Deuteronomy 4, 12-18), 19 X 90 cm, private collection, Jerusalem

Only a Voice relates to the tension between the sense of sight and the sense of hearing. The Biblical text here seems to touch on the roots of the iconoclastic impulse: “And the Lord spoke to you out of the midst of the fire; you heard the sound of words, but saw no form; there was only a voice…Therefore take good heed to yourselves. Since you saw no form on the day that the Lord spoke to you at Horeb out of the midst of the fire, beware lest you act corruptly by making a graven image for yourselves, in the form of any figure, the likeness of any beast that is on the earth, the likeness of any winged bird that flies in the air, the likeness of anything that creeps on the ground, the likeness of any fish that is in the water under the earth.” The painted image is paired with a blank panel, the text with a blank canvas; the two finally meet in the center, yet on the verge of disappearance or birth.

Reading Faces

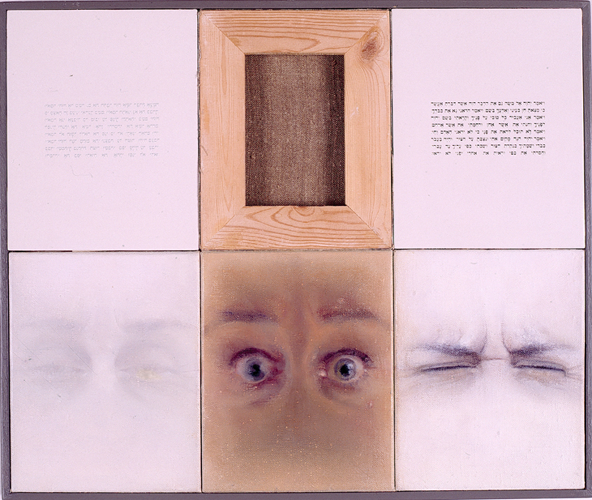

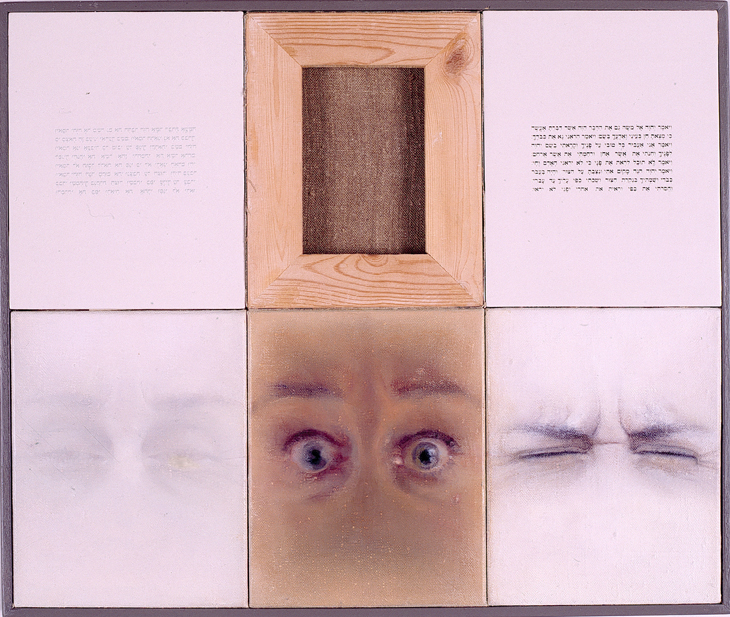

Blind Faith or Seeing is Believing, 1999, oil on canvas and text screen-printed on wood Exodus 33, 17-23), 40 X 45 cm, private collection

The Biblical text in this work describes a dialogue about seeing, between Moses and God: “God said to Moses: Even this thing of which you spoke I shall do, for you have found favor in my eyes, and I have known you by name. He said: Show me now Your glory. He said: I shall make all My goodness pass before you and I shall call out with the name of God before you; …He said: You will not be able to see My face, for no human can see My face and live. God said: Behold! There is a place near Me; you may stand on the rock. When My glory passes by, I shall place you in a cleft of the rock; I shall shield you with My hand until I have passed. Then I shall remove My hand and you will see My back, but My face may not be seen”. The work plays with the idea of seeing “from the back,” with the text appearing at upper left as a dimmed mirror image, like the other side of a page. The canvas on top is also reversed, seen from behind, hinting at a forbidden image. Below, three states of vision: Not seeing, seeing open-eyed though in the shadow, and finally, blind or dying eyes.

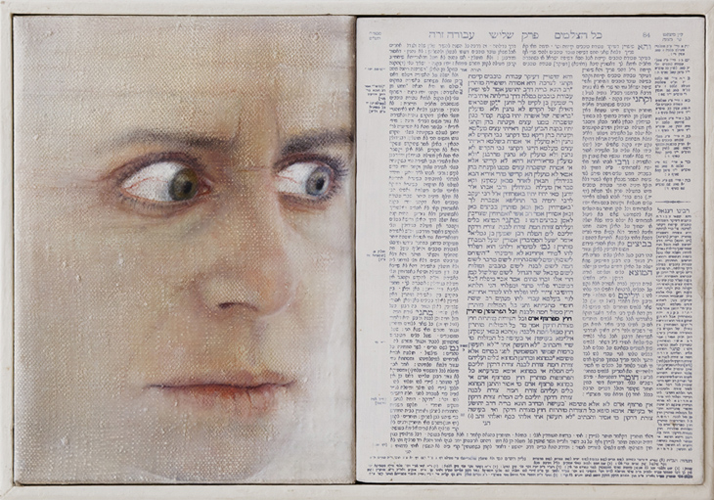

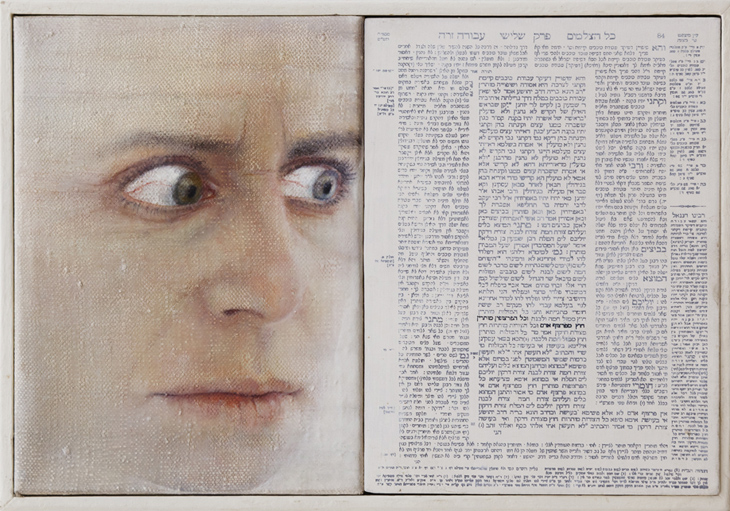

Reading Faces, 1998, oil on canvas and text screen-printed on wood (Talmud Tractate Avoda Zara 42b), 19 X 25 cm, private collection, Jerusalem

In Reading Faces, a painting of my face is juxtaposed with a page of Talmud including an emphasized passage forbidding portraiture: “All faces are permitted except for the human face.” The eyes are looking at the text. A strong visual dialogue and connection are created between them and the text, as between the structure and texture of the text and that of the painted canvas. This dialogue denies the relationship of absolute negation that the words of the text imply.

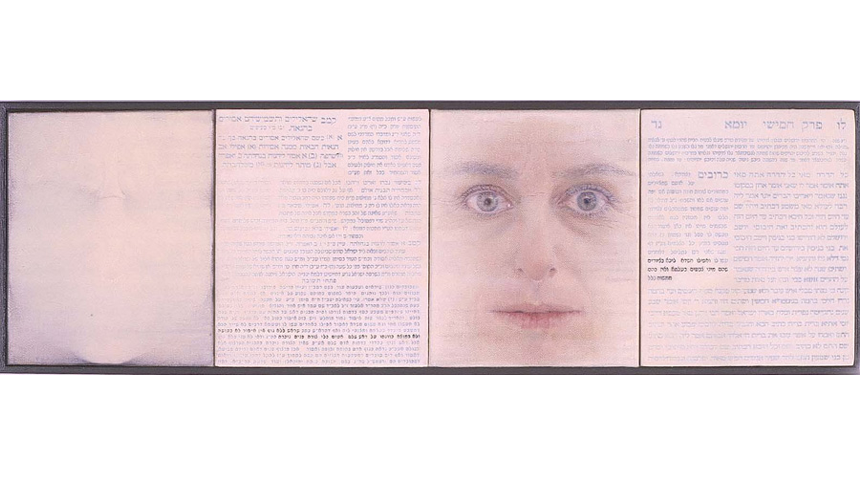

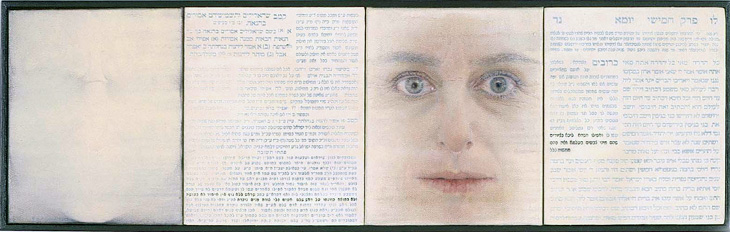

Forbidden Faces, 1999, oil on canvas and text screen-printed on wood (Babylonian Talmud and the Code of Jewish Law), 19 X 60 cm, private collection, Savyon

In this work two medieval texts continue the theme of Reading Faces, the problem of the portrayal of the human face. The emphasized passage on the right reads: “Paintings do not even raise a suspicion, for they are mere colors, and bear no reality whatsoever;” the one on the left reads: “permission to portray a face referred to an indiscrete head, with no recognizable facial features.” The images relate to these statements, but also dispute them – the very real portrait questioning the description of a painting bearing no reality. The painting at left, adhering to the strictest legal instructions, rather than resulting in a weakened, “tamed” image, creates an eerie and unsettling portrait.

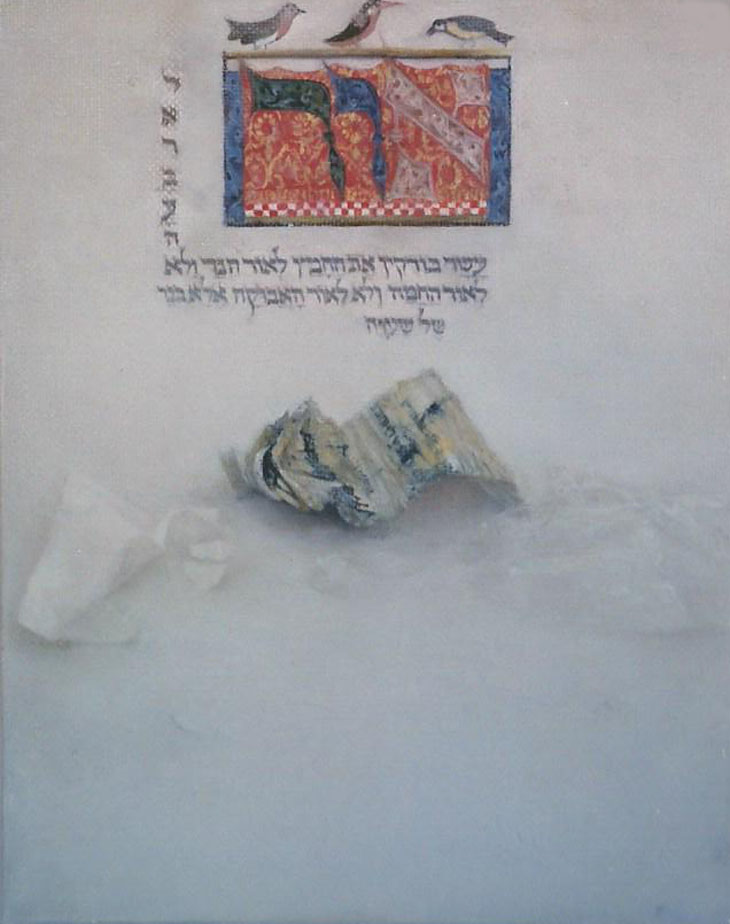

If/ Not, 1999, oil on canvas (based on the Birds’ Head Haggada, 13th century), 50 X 79 cm, private collection, Jerusalem

In the Haggada on which this painting is based, the illuminator chose to paint the heads of the Jews as birds’ heads, probably in order to avoid violating the prohibition on portraying the human face. The painting bears the illusion of an open book, with a painted copy at right of the original page with the song Dayenu (enough). The illumination on this page depicts the Passover sacrifice and the giving of the Torah (with God’s hand emerging from a cloud). On the left-hand side the image is transformed: The ones being burned are the figures of the Jews, and the sacrificial lamb becomes a dog attacking them. As on the right, the hands of the Jews are extended upwards, but the connection with the heavens has been cut off, leaving only the words of the song “And not, and not, and not.” The only figure granted a human face is the cruel perpetrator.

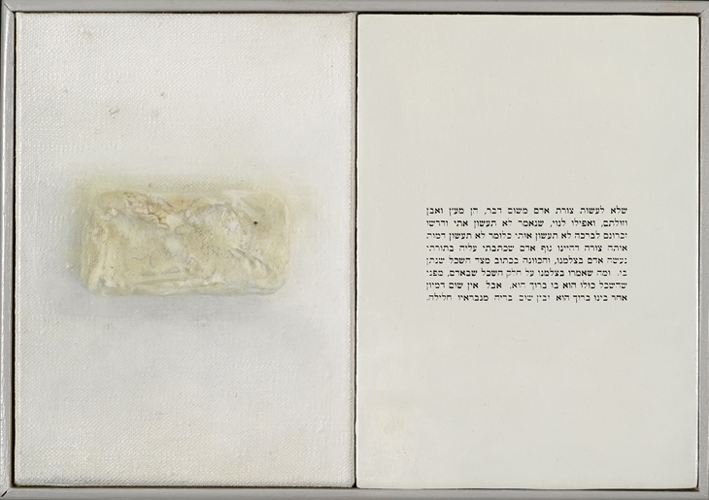

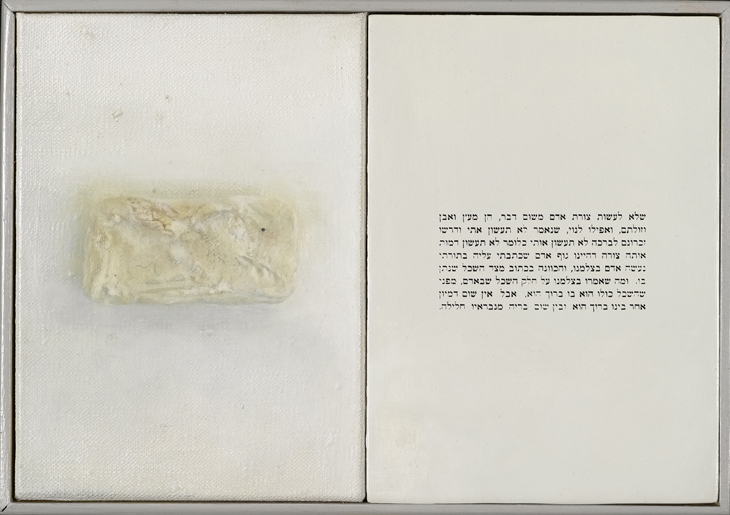

Do Not Make, 1999, oil on canvas and text screen-printed on wood (the Book of Education), 19 X 25 cm

The text at right reads: “Do not make a human figure out of anything, be it of metals, of wood, or anything else…for it is stated ‘You shall not make with Me (Exodus XX: 20),’ and our Sages of blessed memory interpreted it [playing with the similarity of the two words in Hebrew] as ‘You shall not make Me,’ that is not to make anything resembling that form, i.e. the human figure, about which I wrote in My Torah, ‘Let us make man in our image (Genesis I, 26).’…” The text prohibits making of the human form from any material and discusses the meaning of creation of man in God’s image. Next to it is a painting of a bar of soap, echoing one of the difficult memories (whether historical or not) of our century, that of human beings being transformed into soap by other human beings.

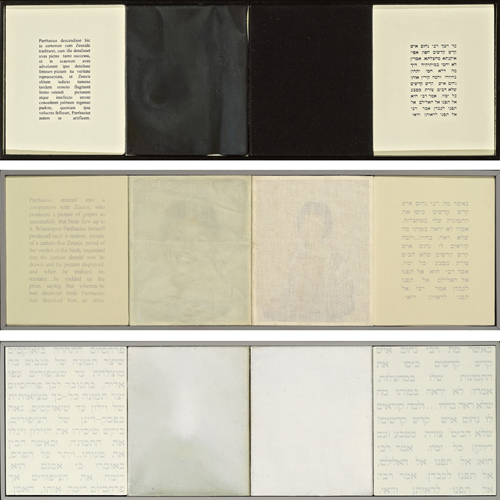

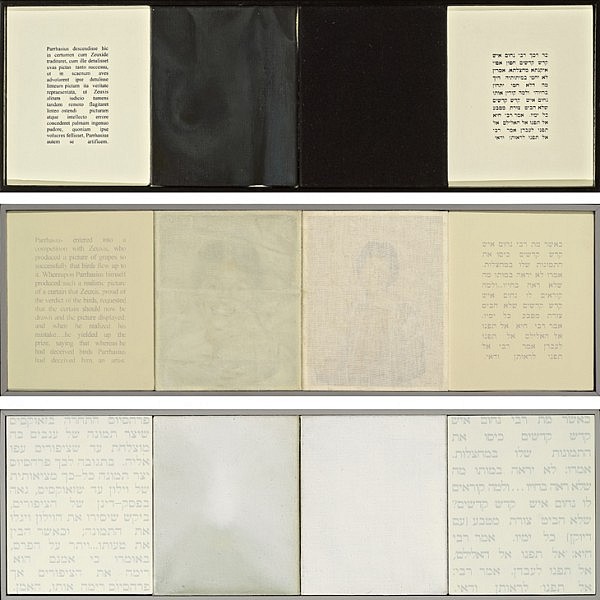

There’s More than One Way to Fight Death (three versions), 1999, mixed media, each part 19 X 60 cm, private collection, California

In this work there is a meeting of texts from different cultures, and of objects and their imitation in painting. The story on the right is from Midrash Kohelet Rabbah (9:10): “When Rabbi Nahum the Man of the Holy of Holies died they covered the pictures in the place with mats and said: ‘As he did not view them in life, so he will not see them in death.’ And why was he called the Man of the Holy of Holies? Because he did not look at a coin [with a portrait] all of his life. Rabbi Hiya said ‘Do not turn to idols (Leviticus 19,4)’ – do not turn to worship them. Rabbi said ‘do not turn to look at them.’” This story hints at the custom that one sees in many Jewish houses of mourning, the covering of mirrors and pictures. Opposite it is another story with a covered picture, one recorded in Pliny (Natural History, 36:35) about a competition between Greek painters over their ability to imitate reality. This story only relates to death in an indirect way, in that our attempts to reproduce reality are in part an attempt to capture and preserve moments of life and protect them from death. In the first version there is a canvas covered with an actual black cloth, and next to it a painting of a black curtain. In the second version is a photograph of my late mother covered with cloth, and next to it a painting of the same covered image, closer. In the third version there is a blank white canvas, and next to it the canvas is transformed into a shroud covering a face. As the images get closer, so do the texts, growing larger while undergoing translation, from Latin and Aramaic to English and Hebrew, and finally to Hebrew alone.

Light

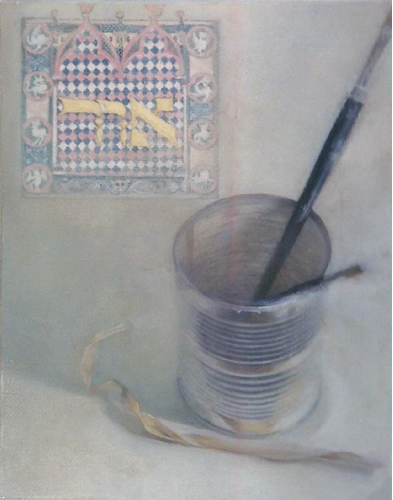

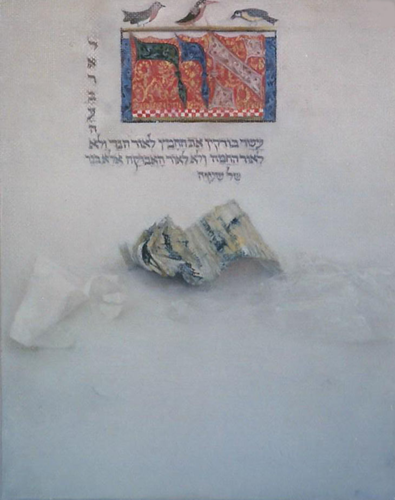

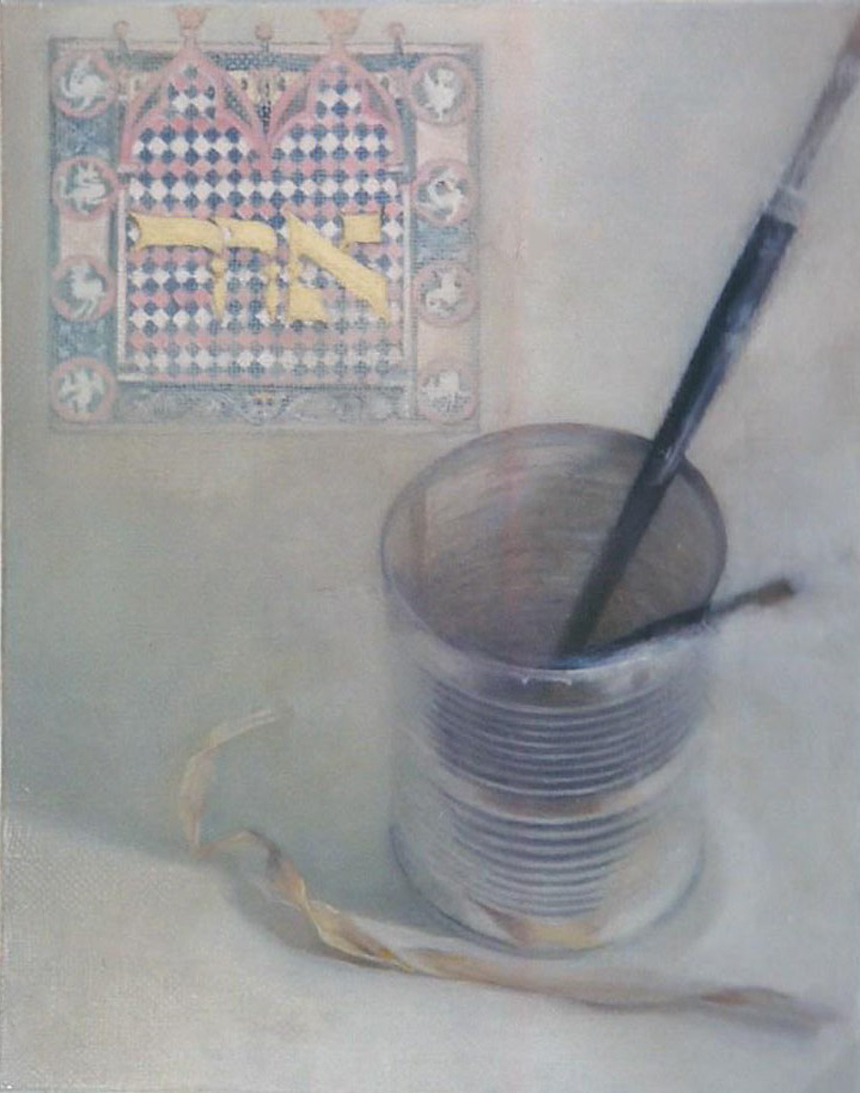

Light 1, 1999, oil on canvas, 24 X 31 cm; still life and painted reference to illuminated Haggada, private collection, Jerusalem

Light 2, 1999, oil on canvas, 24 X 31 cm; still life with painted reference to illuminated Haggada, private collection, Jerusalem

In both of these paintings, segments of ancient Jewish manuscripts with the word light float above studio still life images. The Hebrew alphabet with decorative and symbolic ornament meet the tradition of Western illusionist oil painting.

The Body in the Text

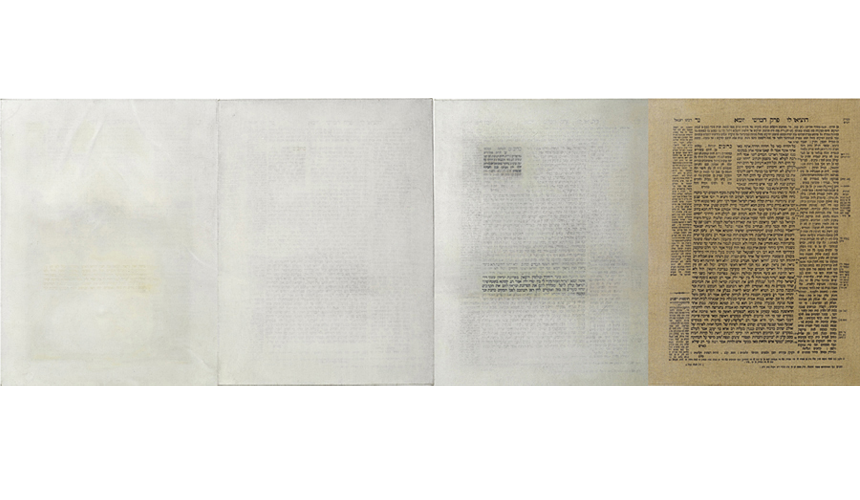

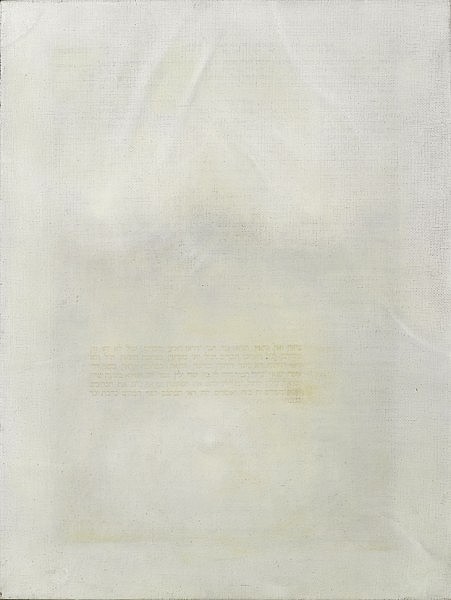

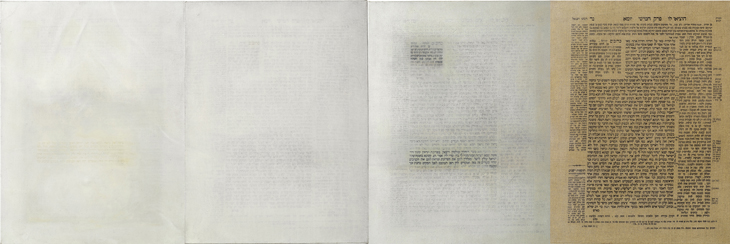

Badim, 1999, oil on canvas (with screen-printed text from the Talmudic tractate Yoma), 53.5 X 162 cm (21″ X 64″), private collection, California

A raw canvas printed with a Talmudic text (at right) is gradually covered, primed white in preparation for painting, as the text disappears. In the left-hand canvas a faint image of a woman’s body appears. On her belly traces of the text reappear, in flesh and canvas tones. The text describes the staves or poles that bore the Ark of the Covenant in the temple, on which stood the sculptures of the Cherubim: “[The staves] probed and protruded outside the curtain like a woman’s breasts…When Israel made pilgrimage to the temple they would roll up the curtain and show them the Cherubim that were intertwined with one another, and they would say to them: ‘Look at the love of God for you, like the love of man and woman.’” The painted image of the woman’s body seems to be pressing through the text, a text written by men; pressing through the curtain, as the text imagines; and pressing through the canvas of the painting. Along with this pressure, the painting seems to open up a possibility of reconciliation between the text and the painting, between spirit and body.